The National Health Service (NHS) in the UK will be unable to handle a pandemic, says Dr Andrew Lawson.

"Towards the end of the film Dr Strangelove, Peter Sellers discusses who will go into the mines to survive. A surreal echo came for myself and colleagues recently when we were in discussions about planning for a bird flu pandemic in the UK as part of an ethics committee.

If a true pandemic of bird flu hits these shores then our notions of what we can expect from the National Health Service will have to change. Some people will have to be denied potentially life-saving treatment: there simply will not be enough beds.

Managing such a pandemic is unimaginable. While it is possible to work out what will happen if a bomb goes off in central London — we can empty intensive care units, mobilise extra staff and stop elective work — what we cannot plan for is 200,000 extra patients who need a life support machine.

Arnie Schwarzenegger, the governor of California, says his state will buy thousands more machines, but who will man them? A gut reaction is to blame the government for underresourcing. It is true that we have a chronic underinvestment in intensive care compared with the United States, Australia or other European countries. In any normal situation such a criticism would be valid, but in a pandemic it becomes a statistical irrelevancy.

Who will decide, and on what criteria, those getting the chance of survival? If you and a friend get bird flu and you both end up in hospital, the estimates are that within 48 hours one of you will need life support. At conservative estimates the need for intensive care will be about two-and-a-half times more than we can provide.

Allocation of such resources will have to be either on a first come first served basis or on an explicitly utilitarian basis of capacity to benefit. This shift from an egalitarian free access to a limited one based on expected outcome represents a profound shift in how we deliver healthcare.

Exclusion criteria have already been drawn up in Canada and the United States and include such contentious issues as restriction based on age or on preexisting disease such as cystic fibrosis or metastatic cancer. Saying “no” to a desperately ill child with cystic fibrosis or to a previously fit 85-year-old is not something we are morally or emotionally prepared for. By an ethical analysis it may be the correct thing to do, but will patients or their relatives be prepared to accept it?

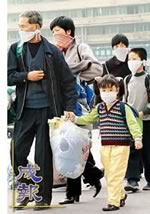

Such arguments may, of course, be purely academic. Assumptions as to what we can do are based on the doctors and nurses, porters and technicians turning up to work. But if we do not have enough masks to protect staff dealing with infected patients, then do the staff have a moral duty to turn up for work and get infected themselves? It may be that they go to work but only once — who will want to return home and potentially infect their own family?

In Victoria, Australia, it was suggested that patients would not go to the GP but to a “flu centre”. The idea that patients would go to where flu is concentrated displays an astounding lack of comprehension of human nature. Similarly, staff will be reluctant to put themselves at risk. HSBC, the banking group, was accused of scaremongering when it announced that perhaps 40% of its staff would not turn up for work in the event of a pandemic, but the NHS may suffer just as badly.

It is not only the risk of infection that may stop staff turning up to work. With such limited access to intensive care, it would be expected that hospitals might not be safe places at all. If I decide not to ventilate someone, his or her relatives might not be too happy. Threats to staff are all too common and many are worried about personal security. Consequently it has been suggested that the decision as to who gets the intensive care bed should be taken away from frontline staff in order to protect them.

At a discussion over how we would react to a biological emergency, where casualties would be decontaminated before we resuscitated them, it was asked who would protect the staff. The answer given was hospital security. Pleasant and helpful as they are, these guys are hardly equipped to deal with an angry mob. One doctor said that the most useful thing staff could be given in such an event was a gun.

Another concern is the legal position of staff who refuse treatment. In the absence of any measures put in place to protect them, one can imagine a raft of legal actions being taken out against them.

If attempting to allocate resources on the basis of capacity to benefit is the right thing to do, then those making the decisions need to be protected, otherwise people will not make the decisions required. Perhaps the only equitable and fair way is to shut the intensive care units and limit treatment to the best we can achieve without artificial ventilation".

Dr Andrew Lawson lectures in medical ethics at Imperial College, London, UK.

Source:

TIMESONLINE (2007). If bird flu grips the nation, doctors will need guns (Electronic version). Retrieved February 12, 2007 http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/health/article1363825.ece

For additional information on Pandemic preparedness from a business continuity perspective, please feel free to contact Pitsel & Associates Ltd. Calgary, Alberta, (403) 245-0550. “The time to plan is when you have time to plan.”

Monday, February 12, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment